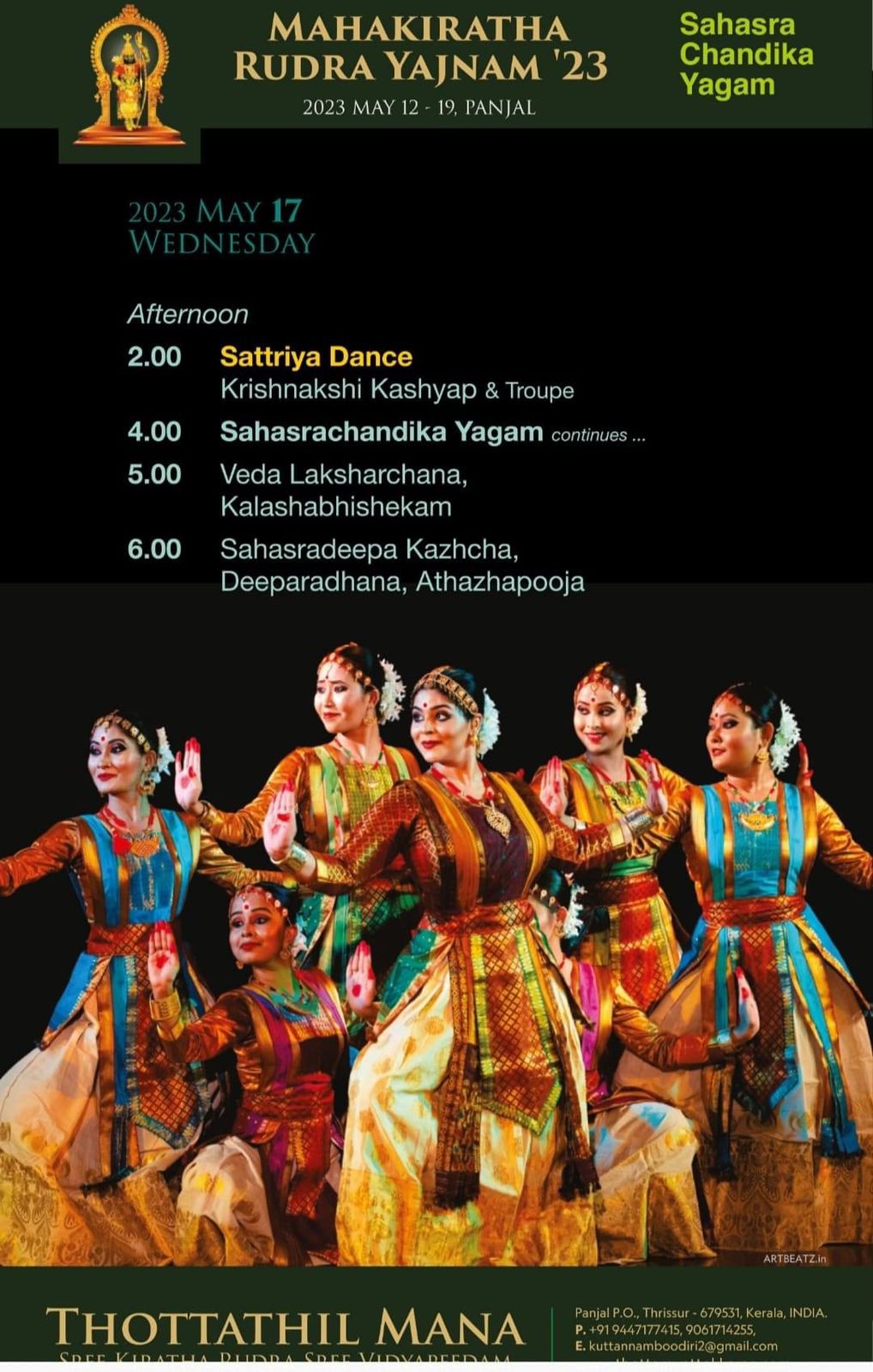

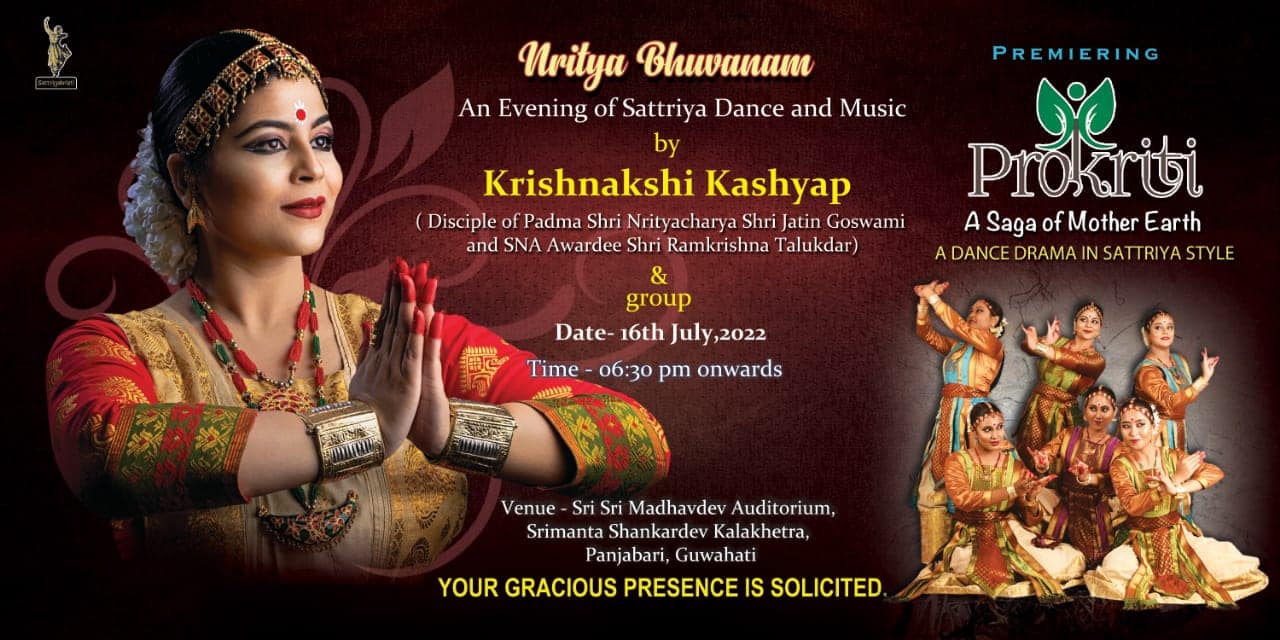

A much-debated move, it is said that he had to leave the Sattra because of this. But now, Sattriya is mostly performed by female dancers, unlike earlier, when it was only performed by male monks. When it was taught to women, few modifications had to be made, mainly in terms of costume. The dance form was also altered to make it suitable for stage. Even in terms of music, everything had to be synchronised and brought in tune to make the presentation more sophisticated. Repetitions were also removed to make different pieces fit for the standard repertoire. But everything was done keeping in mind the traditional boundaries.

What do you think makes Sattriya music unique?

Sattriya music is backed by a rich treasure of literature, written by the two saints, and an independent musical set up with its own taals and raags. There are many raags and taals with names similar to other music styles, but the technique of singing and the taal measurements are quite different. Moreover, in Hindustani music, the sam where geet, badya and nritya coincide is usually in the first taali. But in Sattriya sangeet, sam occurs in the last taali.

You have many choreographic works to your credit that have made a huge impact on the Sattriya repertoire. How do you balance traditional elements and modern sensibilities?

Over the years, I have attempted to create new works to reflect the changing times. Any Sattriya traditional piece includes Ramdani, Geetor Naach and Mela Naach, and at times, just the first two. In these pieces, abhinaya is very limited. But abhinaya is important part of Ojapali dance and some portion of Ankiya Naats. So, there was a need to incorporate Sattriya-based abhinaya compositions in the repertoire and that made me create new works, most of which are based on texts from Sankardeva or pre-Sankardeva era. Whatever be the kind of choreography, Sattriya’s style, music and philosophy should be maintained and the message behind the work should reach the audience.

What are your views on using art to address issues and create social awareness?

The objective of any art form should be the betterment of society. Sattriya dance was introduced to propagate Vaishnava idealogy. Dance will be left without any meaning if a thought-provoking message cannot be put forward through it. And if today, Sattriya dance can be used as a tool to address contemporary social issues that need attention, then it becomes our duty to work on it.

Do you think digital technology and social media have a role to play in popularising ancient art forms?

This dance form survived through the Sattra culture, oral traditions and the guru-shishya parampara. Now in the fast-paced world, digital technology and social media would play a significant role in enabling dance communities to reach out to a larger audience in a very limited span of time, be it through performances, teaching or research.

Looking back at your long journey in dance, what challenges did you face as a young practitioner? Do you think the situation is better today?

We had to face a lot of difficulties. People who didn’t belong to the Sattras were not taught the dance. At times, those who belonged to one Sattra were not allowed to learn at another. Also, it was beyond the society’s imagination that dance could be a profession. So not many were interested. This mindset has changed completely. The government, media and organisations are now patronising and supporting arts, and so, opportunities have certainly increased.

I feel young practitioners should take Sattriya across the globe through performances that are aesthetically appealing and theoretically correct. They should look at art not as entertainment, but as prayer.

The Guwahati-based writer is a well-known Sattriya artiste.